Title

Recall: Example \(\NP\)-complete problem: Boolean satisfiability

A Boolean formula \(\phi\) is satisfiable if there is an assignment of truth values to its variables that makes the formula evaluate to \(1\).

We introduce the Boolean satisfiability problem:

\[ \probSAT = \setbuild{\encoding{\phi}}{ \phi \text{ is a satisfiable Boolean formula }} \]

We know \(\probSAT \in \NP\) because we can easily implement a polynomial-time decider for:

\[ \verifier{\probSAT} = \setbuild{\encoding{\phi, w}}{ \phi \text{ is a Boolean formula, and } \phi(w) = 1 } \]

- Cook-Levin Theorem: \(\probSAT \in \P \iff \P = \NP\).

- In other words: we could prove \(\P = \NP\) by finding a polynomial-time algorithm for \(\probSAT\).

- This is another way of saying \(\probSAT\) is \(\NP\)-complete.

- \(\probSAT\) is “at least as hard” as any other problem in \(\NP\).

Reductions

- The way you show problem \(B\) is at least as difficult as problem \(A\) is by exhibiting a reduction from \(A\) to \(B\).

- Intuitively: we can solve an instance of \(A\) by converting it into an “equivalent” instance of \(B\).

- Provided the conversion process is efficient, a fast algorithm for \(B\) enables an efficient algorithm for \(A\).

- Since our notion of “efficiency” is “computable in polynomial time,” we are specifically concerned with polynomial-time reductions.

Simple reduction example: \(\probIndSet\) to \(\probClique\)

Recall the the \(k\)-clique problem (clique = set of nodes with edges between all pairs): \[ \probClique = \setbuild{\encoding{G, k}}{ G \text{ is an undirected graph with a } k\text{-clique}} \]

We now introduce a closely related problem, the \(k\)-independent set problem (independent set = set of nodes with edges between no pairs): \[ \probIndSet = \setbuild{\encoding{G, k}}{ G \text{ is an undirected graph with a } k\text{-independent set}} \]

Given input \(\encoding{G_i, k}\) for \(\probIndSet\),

how can we convert it to input \(\encoding{G_c, k}\) for \(\probClique\) such that:\[ \encoding{G_i, k} \in \probIndSet \iff \encoding{G_c, k} \in \probClique \]

Definition of polynomial-time reducibility

A function \(f: \binary^* \to \binary^*\) is polynomial-time computable if there is a polynomial-time algorithm that, given input \(x\), computes \(f(x)\).

Let \(A, B \subseteq \binary^*\) be decision problems. We say \(A\) is polynomial-time reducible to \(B\)

if there is a polynomial-time computable function \(f\) such that for all \(x \in \binary^*\):

\[ \fragment{x \in A \iff f(x) \in B} \]

We denote this by \(A \le^\P B\).

\(A \le^\P B\) means: “B is at least as hard as A” (to within a polynomial-time factor).

Example reduction to bound complexity of \(\probClique\)

from itertools import combinations as subsets

def reduction_from_independent_set_to_clique(G: Graph[Node], k: int) -> tuple[Graph[Node], int]:

V, E = G

Ec = [ {u,v} for (u,v) in subsets(V,2)

if {u,v} not in E and u!=v ]

Gc = (V, Ec)

return (Gc, k)

# Hypothetical polynomial-time algorithm for Independent Set

def independent_set(G: Graph[Node], k: int) -> bool:

Gp, kp = reduction_from_independent_set_to_clique(G, k)

return clique_algorithm(Gp, kp)

# Hypothetical polynomial-time algorithm for Clique

def clique_algorithm(G: Graph[Node], k: int) -> bool:

raise NotImplementedError("Not implemented yet...")Recall: definition of polynomial-time reducibility

A function \(f: \binary^* \to \binary^*\) is polynomial-time computable if there is a polynomial-time algorithm that, given input \(x\), computes \(f(x)\).

Let \(A, B \subseteq \binary^*\) be decision problems. We say \(A\) is polynomial-time reducible to \(B\)

if there is a polynomial-time computable function \(f\) such that for all \(x \in \binary^*\):

\[ x \in A \iff f(x) \in B \]

We denote this by \(A \le^\P B\).

\(A \le^\P B\) means: “B is at least as hard as A” (to within a polynomial-time factor).

Which of the following are possible lengths of \(f(x)\)?

- \(\log{|x|}\)

- \(|x|\)

- \(|x|^2\)

- \(2^{|x|}\)

\(|f(x)| \le |x|^c\) if \(f\) is computable in time \(n^c\) for some constant \(c\).

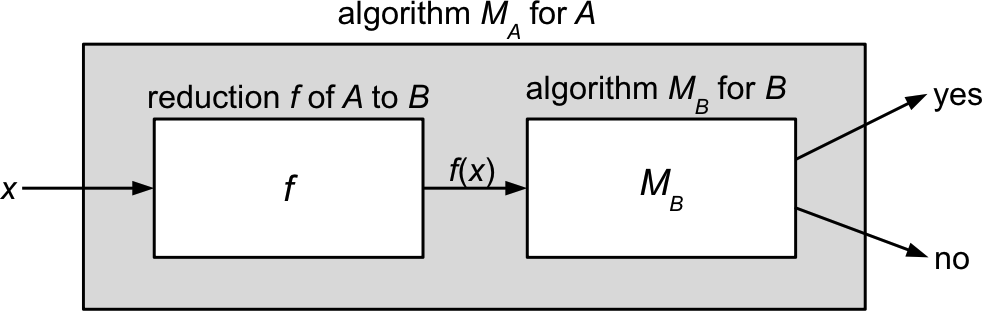

Visual schematic of polynomial-time reduction

\[ A \le^\P B \]

“Reducing from \(A\) to \(B\)”

\[ x \in A \iff f(x) \in B \]

- Needn’t be \(1\)-\(1\) or onto!

- Just needs to map:

- \(x \in A\) to \(f(x) \in B\).

- \(y \notin A\) to \(f(y) \notin B\).

Recall: Example reduction to bound complexity of \(\probClique\)

from itertools import combinations as subsets

def reduction_from_independent_set_to_clique(G: Graph[Node], k: int) -> tuple[Graph[Node], int]:

V, E = G

Ec = [ {u,v} for (u,v) in subsets(V,2)

if {u,v} not in E and u!=v ]

Gc = (V, Ec)

return (Gc, k)

# Hypothetical polynomial-time algorithm for Clique

def clique_algorithm(G: Graph[Node], k: int) -> bool:

raise NotImplementedError

# Polynomial-time algorithm for IndependentSet

# that calls clique_algorithm as a subroutine

def independent_set(G: Graph[Node], k: int) -> bool:

Gp, kp = reduction_from_independent_set_to_clique(G, k)

return clique_algorithm(Gp, kp)

- We conclude that \(\probIndSet \le^\P \probClique\).

- \(\probClique\) is at least as hard as \(\probIndSet\).

- Since

reduction_from_independent_set_to_cliquealso happens to work in the other direction

(just complement again!), we can conclude also: \(\probClique \le^\P \probIndSet\).

Implications of \(A \le^\P B\)

Let’s now formalize what we mean by “\(B\) is at least as hard as \(A\)”

Theorem: If \(A \le^\P B\) and \(B \in \P\), then \(A \in \P\). (“if \(B\) is easy, then \(A\) is easy”)

Proof:

Since \(B \in \P\), there is an algorithm \(M_B\) for \(B\) running in time \(O(n^k)\) for some constant \(k\).

Since \(A \le^\P B\), there is a reduction \(f\) from \(A\) to \(B\) running in time \(O(n^c)\) for some constant \(c\).

We can construct an algorithm \(M_A\) deciding \(A\) simply by composing \(f\) and \(M_B\): \[ M_A(x) = M_B(f(x)) \]

What is the time complexity of \(M_A\)? Let \(n = |x|\).

- \(O(n^c)\) for \(f(x)\), plus \(O(m^k)\) for \(M_B(f(x))\), where \(m = |f(x)|\).

- Since \(m = O(|x|^c)\), the full time complexity is: \[ O(n^c) + O(O(|x|^c)^k) \fragment{= O(n^c + n^{ck})} \fragment{= O(n^{ck})} \fragment{\quad \implies \quad A \in \P} \]

Implications of \(A \le^\P B\)

Let’s now formalize what we mean by “\(B\) is at least as hard as \(A\)”

Theorem: If \(A \le^\P B\) and \(B \in \P\), then \(A \in \P\). (“if \(B\) is easy, then \(A\) is easy”)

- If the fastest algorithm for \(B\) runs in time \(t(n)\), then the fastest algorithm for \(A\) takes no more than \(p(n) + t(p(n))\) where \(p(n)\) is the polynomial running time of \(f\).

- These runtimes are both “polynomially equivalent.”

Corollary: If \(A \le^\P B\) and \(A \notin \P\), then \(B \notin \P\).

This corollary is the way we typically use reductions:

we know/believe \(A\) is hard, and want to show \(B\) is also hard.

Which direction to reduce

Suppose we want to show that \(\probSAT\) is at least as hard as \(\probHamPath\).

Which problem should we reduce to which?

- Reduce from \(\probSAT\) to \(\probHamPath\)

- Reduce from \(\probHamPath\) to \(\probSAT\)

\[ \probHamPath \le^\P \probSAT \]

\[ \probHamPath \overset{f}{\longrightarrow} \probSAT \]

- We equivalently want to show \(\probHamPath\) is “at least as easy” as \(\probSAT\).

- We do this by exhibiting an algorithm for \(\probHamPath\):

- Reduce to \(\probSAT\) via \(f\).

- Run the algorithm for \(\probSAT\).

Reductions between problems of different types

- The reduction from \(\probClique\) to \(\probIndSet\) (and vice versa) was not too surprising since the concepts of cliques and independent sets are closely related.

- But reductions can remarkably creative, drawing connections between seemingly unrelated problems.

- To see this, let’s consider another problem known to be as hard as \(\probSAT\), called \(\probThreeSAT\).

- \(\probThreeSAT\) is a special case of \(\probSAT\) where the Boolean formula is in a special form.

Reductions between problems of different types: \(\probThreeSAT\)

A Boolean formula is in conjunctive normal form (CNF) if it is a conjunction of clauses,

where each clause is a disjunction of literals (“literal” = variable or its negation). Example:

\[ \phi = \underbrace{(x \lor \overline{y} \lor \overline{z} \lor w)}_\text{clause 1} \land \underbrace{(z \lor \overline{w} \lor x)}_\text{clause 2} \land \underbrace{(y \lor \overline{x})}_\text{clause 3} \]

\(\encoding{\phi} \in \probSAT\) iff, for every clause, we can make at least one literal true.

A Boolean CNF formula \(\phi\) is a 3-CNF formula if each of its clauses has exactly 3 literals.

Example: \[

\phi = (x \lor \overline{y} \lor \overline{z}) \land (z \lor \overline{y} \lor x)

\]

\[ \probThreeSAT = \setbuild{\encoding{\phi}}{\phi \text{ is a satisfiable 3-CNF formula}} \]

This turns out to be just as hard as \(\probSAT\)!

Reductions between problems of different types: \(\probThreeSAT\)

\[ \probThreeSAT = \setbuild{\encoding{\phi}}{\phi \text{ is a satisfiable 3-CNF formula}} \]

\[ \probIndSet = \setbuild{\encoding{G, k}}{ G \text{ is an undirected graph with a } k\text{-independent set}} \]

- We’ll now show that \(\probIndSet\) is at least as hard as \(\probThreeSAT\). \[ \probThreeSAT \le^\P \probIndSet \]

- This is not obvious how to do: \(\probIndSet\) involves graphs and \(\probThreeSAT\) involves formulas.

- Our reduction will need to convert clauses of a 3-CNF formula into graph structures.

- These structures built by the reduction are called gadgets

- The literals of the formula will be “simulated” by nodes in the graph.

- The clauses will be “simulated” by triplets of nodes.

Reductions between problems of different types: \(\probThreeSAT\)

\[ \probThreeSAT = \setbuild{\encoding{\phi}}{\phi \text{ is a satisfiable 3-CNF formula}} \]

\[ \probIndSet = \setbuild{\encoding{G, k}}{ G \text{ is an undirected graph with a } k\text{-independent set}} \]

Theorem: \(\probThreeSAT \le^\P \probIndSet\).

Proof:

Given a 3-CNF formula \(\phi\), our reduction must produce a pair \((G, k)\) such that: \[ \encoding{\phi} \in \probThreeSAT \; \iff \; \encoding{G, k} \in \probIndSet \]

Set \(k\) equal to the number of clauses in \(\phi\).

Write \(\phi\) as: \[ \phi = (a_1 \lor b_1 \lor c_1) \land (a_2 \lor b_2 \lor c_2) \land \ldots \land (a_k \lor b_k \lor c_k) \] where \(a_i, b_i, c_i\) are the three literals in clause \(i\).

G will have \(3k\) nodes,

one for each literal in \(\phi\).